© Copyright Peter Crawford 2017

this 'complex' article is under construction - please be patient

The followers of the völkisch movement, including those who supported and created the Third Reich, almost certainly saw their beliefs as a movement toward the 'light', (the renewal of the sun's light being the essence of Spring), and a new and brighter world, which had finally been regenerated and made new.

An essential part of this 'new world' was to be expressed in Nordic-Aryan art.

The art of the late 19th and early 2oth centuries was seen by members of the völkisch movement as 'corrupt' and 'degenerate' - 'Entartete Kunst' - 'degenerate art'.

The period had seen an abandonment of the cannons of 'classical art' and inherited from the Ancient World and the Renaissance, in favor of 'distortion', 'unnatural' and 'violent' color, vulgar and degrading subject matter, and above all - meaningless 'abstraction'.

'Formalism' - the doctrine that states that the aesthetic qualities of works of visual art derive from the visual and spatial properties, was accepted and held to be essential, as long as those 'formal qualities' also expressed certain social, narrative, philosophical or spiritual elements.

Historical Perspective

In the latter part of the 19th, and the early part of the 20th Century Germany and Austria, just as much as France, had been hotbeds of artistic experimentation.

While French impressionism and Post Impressionism had little influence on Germanic art during this period. Germany and Austria had produced their own avant-garde 'art movements'.

It is ironic that, at the time that the young Hitler - an aspiring artist, and Lanz von Liebenfels - author of 'Theozoologie' and the journal 'Ostara', were active in Vienna, the 'Wiener Secession' came into being.

Social Change

The Gründerzeit (the times) in the later nineteenth century in Austria was a period of intensive industrialization, rapid social expansion and financial speculation.

An essential part of this 'new world' was to be expressed in Nordic-Aryan art.

The art of the late 19th and early 2oth centuries was seen by members of the völkisch movement as 'corrupt' and 'degenerate' - 'Entartete Kunst' - 'degenerate art'.

The period had seen an abandonment of the cannons of 'classical art' and inherited from the Ancient World and the Renaissance, in favor of 'distortion', 'unnatural' and 'violent' color, vulgar and degrading subject matter, and above all - meaningless 'abstraction'.

'Formalism' - the doctrine that states that the aesthetic qualities of works of visual art derive from the visual and spatial properties, was accepted and held to be essential, as long as those 'formal qualities' also expressed certain social, narrative, philosophical or spiritual elements.

Historical Perspective

In the latter part of the 19th, and the early part of the 20th Century Germany and Austria, just as much as France, had been hotbeds of artistic experimentation.

While French impressionism and Post Impressionism had little influence on Germanic art during this period. Germany and Austria had produced their own avant-garde 'art movements'.

It is ironic that, at the time that the young Hitler - an aspiring artist, and Lanz von Liebenfels - author of 'Theozoologie' and the journal 'Ostara', were active in Vienna, the 'Wiener Secession' came into being.

Social Change

The Gründerzeit (the times) in the later nineteenth century in Austria was a period of intensive industrialization, rapid social expansion and financial speculation.

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2017 Österreichisches Wappen |

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2017 Stadt Wappen von Wien |

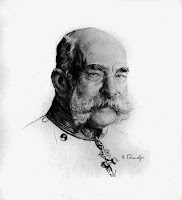

The population of the capital increased from under half a million in the 1850s to over two million by 1910 during the reign of Emperor Franz Joseph, with less than half of its inhabitants born there.

Demographic growth was matched by great technological and scientific advances with the erection of the first electric lights on the Kohlmarkt (1893), the advent of the tram (1894), the vaulting of the river Wien and the regulation of the Danube Canal (1898), and the construction of the city’s metropolitan railway network.

|

| Kaiser Franz Joseph |

The well-known Austrian writer, Stefan Zweig, has described the Viennese’s belief in inexorable ‘progress’ as having the force of a religion.

Security, peace, and prosperity of the ruling classes and the power of the Habsburgs were reflected in the Imperial Jubilee celebrations of 1898.

This marked the fiftieth anniversary of Franz Joseph’s accession to the throne, an ageless figure himself who played a crucial role in creating an illusion of permanence.

Within twenty years, the Dual Monarchy of Austro-Hungary Empire was split into many parts and Vienna reduced to the role of capital of merely the Republic of Austria.

Wiener Secession

The Vienna Secession was founded on 3 April 1897 by artists Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Josef Hoffmann, Joseph Maria Olbrich, Max Kurzweil, Wilhelm Bernatzik and others. Although Otto Wagner is widely recognised as an important member of the Vienna Secession he was not a founding member.

The Secession artists objected to the prevailing conservatism of the Vienna Künstlerhaus with its traditional orientation toward 'Historicism' (and aspect of which Hitler, on the other hand, approved).

Interestingly, many of the Secession artists, before joining the group, had been exceptionally fine 'classical' artists - and this was particularly true of Klimt, who is now only remembered for his Secession paintings which, while being startling, in color, design and technique, show little of the superlative 'painterly' skill ('malerische Geschick') that Klimt possessed.

The Berlin and Munich Secession movements preceded the Vienna Secession, which held its first exhibition in 1898.

|

| 'Wandern im griechischen Theater' (fresko) Gustav Klimt |

The Berlin and Munich Secession movements preceded the Vienna Secession, which held its first exhibition in 1898.

The group earned considerable credit for its exhibition policy, which made the French Impressionists somewhat familiar to the Viennese public.

The 14th Secession exhibition, designed by Josef Hoffmann and dedicated to Ludwig van Beethoven, was especially famous.

The 14th Secession exhibition, designed by Josef Hoffmann and dedicated to Ludwig van Beethoven, was especially famous.

On 14 June 1905 Gustav Klimt and other artists seceded from the Vienna Secession due to differences of opinion over artistic concepts.

Secession Style & Philosophy

Unlike many other movements, there is not one style that unites the work of all artists who were part of the Vienna Secession.

The Secession building could, however, be considered the icon of the movement.

|

| Secession Building |

|

| 'Ver Sacrum' |

Secession artists were concerned, above all else, with exploring the possibilities of art outside the confines of academic tradition.

They hoped to create a new style that owed nothing to historical influence.

In this way they were very much in keeping with the iconoclastic spirit of turn-of-the-century Vienna.

In this way they were very much in keeping with the iconoclastic spirit of turn-of-the-century Vienna.

The Secessionist style was exhibited in a magazine that the group produced, called 'Ver Sacrum', which featured highly decorative works representative of the period.

In many ways the 'Werkstätte' was a beak away movement from the Secession, in that it favoured a more 'modernistic' style.

German Fin-de-siècle

Unlike Austria, Germany was not an ancient Empire, but rather a 'new nation', somewhat unsure of its new identity, and led by a young ruler (Kaiser Wilhelm II) who was far from stable or assured about his own identity.

Wilhelm II, like the young Hitler, had artistic pretensions - although in terms of collecting rather that practicing.

Wilhelm, however, partly because of his physical disability, felt called upon to present a 'macho' facade, and kept much of his 'artistic' interested well hidden, from all but his closest associates - and they were very few in number.

Both Hitler and Wilhelm II had a great respect for traditional art and architecture, and were obsessed with the classical past.

By the end of the Nineteenth Century, more artists lived in Munich than lived in Vienna and Berlin put together, however, the art community there was dominated by the conservative attitudes of the 'Münchener Künstlerverein', and its supporters in the government.

The 'Münchener Secession' was an association of visual artists who broke away from the mainstream 'Münchener Künstlerverein' in 1892, to promote and defend their art in the face of what they considered official paternalism, and its conservative policies.

German Fin-de-siècle

|

| Kaiser Wilhelm II |

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2017 Wappen des Deutschen Reiches |

Wilhelm II, like the young Hitler, had artistic pretensions - although in terms of collecting rather that practicing.

Wilhelm, however, partly because of his physical disability, felt called upon to present a 'macho' facade, and kept much of his 'artistic' interested well hidden, from all but his closest associates - and they were very few in number.

Both Hitler and Wilhelm II had a great respect for traditional art and architecture, and were obsessed with the classical past.

Adolf Hitler's favorite artist - prior to the 'Great War' - was Hans Makart - (28 May 1840 – 3 October 1884) an Austrian academic history painter, designer, and decorator; most well known for his influence on Gustav Klimt and other Austrian artists, but in his own era considered an important artist himself, and a celebrity figure in the high culture of Vienna, attended with almost cult-like adulation. He went to Munich, and after two years of independent study attracted the attention of Karl Theodor von Piloty, under whose guidance, between 1861 and 1865 he developed his painting style. During these years, Makart also travelled to London, Paris and Rome to further his studies. His work engendered the term "Makartstil", which completely characterized the era. The "Makartstil", which determined the culture of an entire era in Vienna, was an aestheticism the likes of which hadn't been seen before him, and has not been replicated to this day. Called the 'Magier der Farben' - (magician of colors), he painted in brilliant colors and fluid forms, which placed the design and the aesthetic of the work before all else. Klimt's early style is based in 'historicism' and has clear similarities to Makart's paintings

'Abundantia - Die Geschenke der Erde'

Münchener Secession

The 'Münchener Secession' was an association of visual artists who broke away from the mainstream 'Münchener Künstlerverein' in 1892, to promote and defend their art in the face of what they considered official paternalism, and its conservative policies.

They acted as a form of cooperative, using their influence to assure their economic survival and obtain commissions.

In 1901, the association split again when some dissatisfied members formed the group 'Phalanx'.

Another split occurred in 1913, with the founding of the 'Neue Münchener Secession'.

The most influential and talented member of the Münchener Secession was Franz von Stuck, who was, somewhat surprisingly, much admired by Adolf Hitler.

Berliner SecessionThe most influential and talented member of the Münchener Secession was Franz von Stuck, who was, somewhat surprisingly, much admired by Adolf Hitler.

Franz Ritter von Stuck

'Athlet'

Franz Stuck (February 23, 1863 – August 30, 1928) was a German painter, sculptor, engraver, and architect. In 1906, Stuck was awarded the 'Verdienstorden der bayerischen Krone', and was henceforth known as Franz Ritter von Stuck. In 1892 Stuck co-founded the Münchener Secession, and also executed his first sculpture, 'Athlet'.

The next year he won further acclaim with the critical and public success of what is now his most famous work, the painting 'Die Sünde'. Stuck's subject matter was primarily from mythology, inspired by the work of Arnold Böcklin (another of Hitler's favorite artists). Large forms dominate most of his paintings, and indicate his proclivities for sculpture. His seductive female nudes are a prime example of popular 'Symbolist' content. Stuck paid much attention to the frames for his paintings and generally designed them himself with such careful use of panels, gilt carving and inscriptions that the frames must be considered as an integral part of the overall piece. Ritter von Stuck's 'Kämpfende Amazone', created in 1897, graced Hermann Göring's residence 'Carinhall'.

'Die Sünde'

The 'Berliner Secession' was an art association founded by Berlin artists in 1898 as an alternative to the conservative state-run 'Verein der Berliner Künstler'.

That year the official salon jury rejected a landscape by Walter Leistikow, who was a key figure among a group of young artists interested in modern developments in art.

Sixty-five young artists formed the initial membership of the Secession.

The biggest conflict in the Berlin Secession was over the question of whether it should follow the new wave of 'Expressionismus'.

Expressionism was a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it radically for emotional effect in order to evoke moods or ideas. Expressionist artists sought to express the meaning of emotional experience, rather than physical reality - and were prepared to break all the conventions of classical art. Generally, expressionism was not popular with the vast majority, and was always (and still is) an acquired taste - often used by the intelligentsia (and pseudo-intelligentsia) to differentiate themselves from the 'common herd'. Expression was (and is) an easy target for those opposed to 'Entartete Kunst', despite the fact that some art works, approved by the Third Reich, exhibited some Expressionist tenancies, (this particularly applies to certain examples of sculpture).Prominent artists of the 'Berliner Secession' were Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) Max Klinger (1857–1920) Max Liebermann (1847 – 1935) Georg Kolbe (1877 – 1947) Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880 – 1938) Edvard Munch (1863 – 1944)

Max Liebermann (20 July 1847 – 8 February 1935) was a German-Jewish painter and print-maker, and one of the leading proponents of Post Impressionism in Germany.

'Im Schwimmbad'

Max Liebermann

Georg Kolbe (15 April 1877 – 20 November 1947) was the leading German figure sculptor of his generation, who worked in a vigorous, simplified classical style.

Sculpture for the 'Barcelona Pavilion'

Georg Kolbe

Edvard Munch (1863 – 1944) - was a Norwegian painter and print-maker, whose treatment of psychological themes built upon some of the main tenets of late 19th-century 'Symbolism', and greatly influenced German 'Expressionism' in the early 20th century. One of his most well-known works is 'The Scream' of 1893.

Fritz Klimsch (10 February 1870, Frankfurt am Main – 30 March 1960, Freiburg) was a German sculptor. Klimsch studied at the 'königlich Hochschule für die Akademischen Bildenden Künste' in Berlin, and was then a student of Fritz Schaper. In 1898 Klimsch was a founding member of the Berlin Secession. Despite his membership of the 'Berliner Secession', in the era of National Socialism Klimsch was highly regarded as an artist - doubtless because of his modernistic classical style.

'Der Gott Merkur'

Fritz Klimsch

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (6 May 1880 – 15 June 1938) was a German expressionist painter and print-maker, and one of the founders of the artists group 'Die Brücke', a key group leading to the foundation of Expressionism in 20th-century art. He is a good example of the 'unacceptable' face of 'so called' modern art for the opponents of 'Entartete Kunst'.

'Potsdamer Platz'

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Lovis Corinth (1858 – 1925) was a German artist and writer whose mature work as a painter and print-maker realized a synthesis of impressionism and expressionism.

'Diogenes' - (detail)

Lovis Corinth

Max Klinger (18 February 1857 – 5 July 1920) was a German symbolist painter, sculptor, print-maker, and writer. He began creating sculptures in the early 1880s. He was one of the most influential members of the 'Berliner Secession'. Klinger greatly admired the work of the symbolist artist, Arnold Böcklin - who was another favorite artist of Adolf Hitler, and Hitler acquired Böcklin's 'Die Toteninsel' in 1933 where it hung first in the Berghof and later in the Neue Reichskanzlei.

'Die Sirene'

Max Klinger

'Die Toteninsel' - Version III - 1883

Arnold Böcklin

No comments:

Post a Comment